The following article first appeared in 1984 as a contribution to the Les Dossiers H (L’Age d’Homme) consecrated to René Guénon and the theses first developed here were later taken up again and further developed in his Problèmes de la Gnose (2007).1 As the title suggests, it can also implicitly be read as an answer to Maritain’s (in)famous rejection of Guénon (and by extension that of the whole Catholic intelligenzia), who couldn’t see in his doctrine anything other than “the ancient Gnosis” which is “the mother of all heresies”. Since it is a comparatively long text (occupying 31 pages in the original publication), let us furnish a brief summary, so that the reader may find some orientation (and, if he so needs to, skip around).

The first chapter deals with the history of what has come to be known as “Gnosticism”, its origins, and historiography, and then proceeds to demonstrate how “gnosis” (truly so called) is essentially a Christian, or more precisely “Christic” phenomenon and how the religious significance of the term was originally of Pauline origin.

The second chapter deals with the emergence of neo-Gnosticism in the modern era and with the meaning of Guénon’s involvement in the occultist milieu of his time. It ends with a closer look at his early article The Demiurge, in which the curcial role of informal manifestation or the “intelligible world” is brought to light.

Finally, the third chapter, which constitutes the essential core of the essay, begins by retracing the “betrayal of gnosis”, from the side of Aristotelian naturalism on the one side and religious exoterism on the other, arguing (contra Maritain and others) that Guénon’s work is indeed of a central importance for its authentic retrieval. It then enganges in an exegesis of the “metaphysics of knowledge” put forth by Guénon in his Multiple States of the Being and seeks to illuminate the “Mystery of infinite Gnosis” …

Gnosis & Gnosticism in René Guénon

One might think that the question of gnosis and Gnosticism occupies only a very secondary place in René Guénon’s work. And, if we stick to the texts, this is quite true, since he did not expressly devote any article to this question.2 However, if one observes that gnosis designates nothing else than metaphysical knowledge or sacred science, one must admit that Guénon deals, so to speak, with nothing else, and that it represents the essential axis of his entire work. It is of pure and true gnosis, such as Guénon tried to communicate to us, that we would like to speak here, because we believe that there is no notion that is, in the West, more misunderstood than this one, as the attentive study of European theology and philosophy has convinced us.

One of the major reasons for this almost complete misunderstanding is that, as we have already pointed out, the term gnosis was discredited from the very outset by the deviant use made of it by certain philosophical-religious schools of the second century A.D. which, for this reason, have been classified under the general denomination of Gnosticism. From the point of view of the Christian faith, the two things seem to be so closely linked that the one cannot be conceived without the other, and it’ll be asserted that there is in reality no other gnosis than the one exemplified by the Gnosticism of a hundred faces. But, by a consequence which is not at all surprising, the opponents of Christianity will adopt the same attitude, and will claim that in Gnosticism, which they identify with the true gnosis, they possess a tradition prior to and superior to any revealed religion.

Moreover, it is not only Christianity and anti-clericalism that profess the confusion of gnosis and Gnosticism; did not Guénon himself, in the first part of his adult life, work to resurrect Gnosticism, at least in its Cathar form, by participating in the constitution of a Gnostic “Church”, of which he was (validly or not) one of the bishops? He who always seemed to want to make a distinction between the purity of gnosis and the impurities of Gnosticism, was he himself not a member of a neo-Gnostic organization, the alleged heir of an ancient tradition, animated by an unequivocal anti-Catholicism?

Was there a change in Guénon’s attitude? Or should we admit that, as he himself wrote to Noëlle Maurice-Denis Boulet, he “only entered this milieu of Gnosis to destroy it”3? We shall see that, if we stick to the texts, there has indeed been a change, at least in certain respects, which yet doesn’t exclude all continuity. We believe that, as far as the essential doctrine of pure metaphysics is concerned, Guénon has never varied, for the reason that such a variation is simply impossible: what the intellect perceives is, in its most radical essence, immutable evidence. It is not even surprising that such a perception should appear in a young man; on the contrary, it is normal: the young soul is almost naturally open to the lights which radiate from the Holy Spirit4, whereas with age there almost always comes a hardening and forgetting. Yet, the forms in which one tries to express these intuitions can vary considerably, because every language is dependent on a culture, and thus on a history, that is to say, on a dialectic and a problematic, possibly inadequate and always “complicating”. The choice of expressions is thus a calculation of opportunity which is almost impossible to win and which itself depends on one’s knowledge of this culture and history. Such a knowledge, pertaining to facts, can only ever be progressive and empirical; it also depends, and necessarily so, on a certain affinity of the knowing subject with the object known. Hence, apart from religious orthodoxy which is guaranteed by the authority of the magisterial Tradition, the meaning of any cultural form cannot be immutably defined; it changes with the accuracy of our information and our individual predispositions, or it can even be definitively suspended when the question becomes decidedly too muddled. And we know that Guénon never lingered where it did not seem possible for him to obtain a sufficient light.5

The preceding considerations dictate our plan. First of all, we must ask ourselves about the true nature of the historical phenomenon that was gnosis and Gnosticism, because, in this field in particular, partisan passions too often compete with ignorance. We will then be able to better appreciate what the “gnosticizing” period of René Guénon (between 1909 and 1912) was all about, which will be our second concern. Finally, we will try to show why the “Guénonian” gnosis is precisely not Gnosticism, for this is the essential point, and perhaps it has thus far never been sufficiently explained.

I. Gnosis in its History

It is not our intention to deal here with the history of Gnosticism. The subject is so vast and complex that it would require an entire volume. There are also many good presentations on this difficult question already.6 We would merely like to propose a point of view on the genesis of this religious phenomenon that will allow us to acquire a synthetic understanding of it, which requires that we first recall some elementary historical data. Whatever the reservations that must be made with regard to some of the conclusions that have been drawn from it, we nevertheless consider the knowledge of history to be rigorously indispensable in this matter, especially since, as we have emphasized elsewhere7, the history of Gnosticism is inseparable from its historiography (or sometimes even reduced to it). This historiography is moreover very recent — the oldest studies do not go back further than the 17th century8 — and only really took shape in the 19th century, especially thanks to the work of the German historian Harnak (1851-1930). Since then, the most important scholars have not ceased to be fascinated by this question, which has become one of the major problems of the history of religions. In 1945, this interest was to benefit from one of the most extraordinary discoveries of Christian archaeology, that of a library at Nag Hammâdi (Khenoboskion) in Upper Egypt9: when a buried jar was dug up “by accident”, 13 volumes in the form of codexes (i.e., assembled notebooks and not scrolls or volumen10) were discovered which “assemble a total of fifty-three writings, most of which were Gnostic, according to the most recent evaluations”11, and which, for the first time, made it possible to have a direct access to these texts. Until then, in fact, all that was known about those whom one called “the Gnostics” was reduced to quotations and summaries made by the heresiologists (primarily St. Irenaeus and St. Hippolytus) or to a few fragments whose interpretation proved difficult. However, despite all that, the question of Gnosticism is far from being definitively clarified or having been fundamentally transformed.

What is it that we’re dealing with?

To tell the truth, it is not possible to answer this question. It could be, if there really were schools of thought giving themselves the title of Gnostics and characterized by a well-defined body of doctrines. But this is not the case. The term “Gnosticism” is of recent origin and does not seem to predate the beginning of the 19th century. That of “gnostic” (gnostikos), a Greek adjective meaning, in the ordinary sense, “the one who knows”, the “savant”, is only rarely used to technically characterize a philosophical-religious movement: of all the Gnostic sects, only the Ophites have been referred to in this way.12 This is why it was possible to conclude: “There is no trace, in primitive Christianity, of ‘Gnosticism’ in the sense of a vast historical category, and the modern use of ‘Gnostic’ and ‘Gnosticism’ to designate a religious movement that is both broad and ill-defined, is totally unknown among the first Christians.”13 Certainly, when historians apply this religious category to this or that doctrine, it is not absolutely without reason: here and there we find common religious elements and themes, the two most constant of which seem to be the condemnation of the Old Testament and its God on the one hand, and that of the sensible world on the other. However, the use which historians make of these categories is necessarily dependent on the ideas that they have formed of them, that is to say, ultimately, on their conception of gnosis itself and on what they are able to understand of it. Insofar as gnosis also connotes the idea of a mysterious and salvific knowledge, communicated to only a few and under the veil of symbols, bringing into play an extremely complex cosmology and anthropology, and only realizing itself through a kind of dramatic theo-cosmogony, the concept of gnosis takes on a considerable extension. The historians will then be justified to discover it in rather unexpected areas. In the end, it is religion itself, whatever its form, that will be identified with gnosis.

Is it nevertheless possible to find a fixed and indisputable point of reference? Couldn’t the word gnosis itself provide it to us?

This term, in Greek, means knowledge. But it is very rarely used alone, and almost always requires a noun to complement it (the knowledge of something), whereas epistêmê (science) can be used absolutely. That is why, one will admit with R. Bultmann, that gnôsis means, not knowledge as a result, but rather the act of knowing.14 Contrary to what some ignorant people affirm, it is not the only name that the language possesses to express the same idea.15 Plato and Aristotle also use, in related senses, besides epistêmê (and the verbs epistasthaï or eidenaï), dianoia, dianoesis (and dianoesthaï), gnomè, mathèma, mathèsis (and manthaneï), noèsis and (noeïn), noèma, nous, phronésis, sophia, sunésis, etc. Beside this ordinary use of the term, can one speak, as Bultmann does16, of a “gnostic” use, in which it would be employed absolutely, in the sense of “knowledge par excellence”, i.e. the “knowledge of God”? The examples provided by “pagan” literature are hardly conclusive. This is no longer the case with the sapiential literature of the Old Testament in its Greek version (the so-called “Septuagint”). Here, for the first time and in an undeniable way, the verb ginôskô which translates the Hebrew yd’ (also rendered, but more rarely, by eidenaï and epistasthaï) and the noun gnôsis, acquire “a much more accentuated religious and moral meaning in the sense of a revealed knowledge whose author is God or sophia”17. Thus the Bible speaks of God as “the God of gnosis” (I Sam., II, 3). Why did Alexandrian Judaism choose this term (and not, for example, epistêmê) to express the idea of a sacred and unitive knowledge in which the whole being participates? Should we see in this the influence of a mystical (or mysteric) Hellenism which would have already used this term in this sense ? For reasons of principle — and not only of facts, which are always debatable — we do not believe so: it’s inadmissable that a religion could undergo such an alteration of what’s essential for it, namely the unique and mysterious relation which is established between the human being and God in an incomparable act, to which it gives precisely the name of “knowledge”. It is rather the reverse which is true, it is the Jewish tradition which gives the Greek term its full religious meaning18, and if the term chosen to express this act of “knowledge” was that of gnôsis, it is precisely because it was of neutral meaning, whereas a term like epistêmê, which already had a very precise philosophical meaning, would not have lent itself to such an operation. We do not in any way deny the existence of a religious Hellenism or of an Egyptian tradition, these being the two sources that historians have proposed for the Biblical gnosis. On the contrary, the existence of such sacred phenomena is obvious to us. But, as we have pointed out in another work19, it would be good if historians would stop thinking within the sole category of “influence” which inevitably leads them to that of “sources”. There is perhaps no field where such a search is more futile than that of gnosis and Gnosticism. There can be, from one tradition to another, influence, borrowing, transfer, etc., when it comes to peripheral elements, but not for what’s essential to these traditions, at least while they are still alive.

However, if we look at the texts (especially the Book of Proverbs where gnôsis is most often used), we are not yet dealing with gnosis in the sense in which we usually understand it, that is to say, in the sense of a purely interior and deifying knowledge which is no longer only an act but also a state, and which God alone can confer on the pneumatized intellect20: the “charism of gnosis”, as we might call it. Not that the thing doesn’t exist in the Old Testament, but the term gnosis does not receive such a meaning there.21 We must therefore wait for the New Testament, and particularly the First and Second Epistles to the Corinthians, the Epistle to the Colossians and the First to Timothy, to see the word gnosis used for the first time in the sense we have just defined. That the decision to designate the state of spiritual knowledge in this way originated in the Septuagint version is obvious, and there is no need to appeal to Hellenistic culture. But that it was the teaching of Jesus Christ and the revelation of the divine Logos in him that made possible the manifestation of this state of gnosis in the souls of those who believed in him is no less indisputable for us. The whole of Christianity is, in its essence, a message of gnosis: “to know and adore God in spirit and in truth”, and not only through sensible or ritual forms; or rather, to unite oneself to Jesus Christ, who is himself the gnosis of the Father, and who transcends both the created world and religious obligations. Certainly, the word is of Hellenic-Biblical origin. But the thing, the interior and salvific knowledge, the charism of gnosis in which faith reaches its deifying perfection, is simply and fundamentally “Christian”. It is this kerygma of love and transforming union with God that Jesus came to reveal, and it is enough to read the Gospel to realize this. Faced with the ritualism of the Pharisees, Christ, the incarnate gnosis of the Father, comes to reopen the “narrow gate” of spiritual interiority. And how else could the Apostles, and St. Paul and the first Christians have lived their deepest commitment “in Christ”?22

This is why there is no documentary evidence of the existence of a “gnosis” so called, prior to the New Testament, and this in spite of the research (and sometimes the assertions) of eminent historians23. It is true that of the 29 occurrences of gnôsis in the New Testament, not all designate a spiritual state. However, each time they have a religious meaning (except for the first Epistle of St. Peter, III, 7) and if the “gnostic” meaning is above all Pauline24, it also seems to us to be present in St. Luke, when Christ declares: “Woe to you, Doctors of the Law, because you have taken away the key of gnosis; you yourselves have not entered, and those who were entering you have driven out” (XI, 52), especially if one admits that the true key is gnosis itself, which is in reality identified with the “Kingdom of Heaven” as the parallel passage in St. Matthew (XVI, 19) proves. It seems certain to us, therefore, that if there has been a “gnosis” (so called), it was first of all Christian, and even more so “Christic”. One would have to be blind to the “phenomenon” of Christ not to notice the prodigious spiritual effect he must have produced on those who witnessed it first hand (an effect which, two thousand years later, has not yet been exhausted). How can we doubt for a single moment that this Jesus Christ who was “more than a prophet” did not communicate to those he met and who accepted his word, a gnosis, a state of interior and deifying knowledge, that had no common measure with anything they had experienced before? It is this spiritual state that St. Paul designates by the name of gnosis, and in which he sees the perfection of faith.25 It is this that we find in the writings of Pauline inspiration, such as the Epistle of Barnabas — sometimes counted among the New Testament texts — in which the author declares that, if he writes to his interlocutors who already abounds in faith, it is “so that, with the faith you possess, you may have a perfect gnosis”26. That is why St. Paul can say, at the interval of a few lines (1 Cor., VIII, 1-7): “We all have gnosis” and “not all have gnosis”, according to whether it is simple theoretical knowledge which, as such, is “ignorant” and full of itself, or an effective realization of its transcendent and divine nature which protects it from all “external” attack (learned ignorance).

It remains to be asked why St. Paul is, so to say, the only New Testament writer to speak of gnosis, and why St. John totally ignores this term27, although he can rightly be considered the most “gnostic” of all the authors of the New Testament? The answer is, that this is proof of the influence of the LXX Bible, which, as we have seen, was the first to give this term an essentially religious connotation. A man as well versed in the rabbinic science as St. Paul must have been particularly sensitive to this influence. More, certainly, than a St. John, whose knowledge originates in the direct vision of the incarnate gnosis, Jesus Christ, and who, in order to express himself, essentially makes use of the great traditional symbols rather than of concepts.28 However, this particular situation of St. Paul would not suffice to explain the near absence of gnosis in the Gospels. We believe that another, deeper and less circumstantial reason must be added. It is that, among the founding authorities of Revelation recognized by Christian dogmatics, St. Paul occupies a very curious place. He is certainly a major authority, one of the “pillars of the Church”, the depositary of the authentic message, and yet he never “knew Christ in the flesh”! Every Christian must believe that the whole of Revelation was given in Jesus Christ and that the Apostles are the authorized depositories of it only because they received it. Given the supernatural character of this Revelation, it necessarily comes from outside: fides ex auditu, as St. Paul says himself. Compared to this direct revelation (written or oral) which alone is authoritative, there can only be private revelations (devoid of the authority of faith) or theological commentaries which explain the revealed fact. That St. Paul, like any other Christian, received teaching from the Apostles is undeniable. However, among all those who have received such teaching, he is the only one whose word has the value of revelation. And this is because he furthermore received the revelation of the Gospel directly from the Lord (I Cor., XI, 23). It confirms or completes the Apostolic tradition, but the mode of its communication can only be interior.29 Christian dogmatics therefore admits that there can be at least one revelation which comes not only from the “historical” Christ, but also from the interior Son whom God, as St. Paul tells us, “has revealed in myself” (Galatians, I, 17). In other words, it admits that there can be a “spiritual experience” that is worthy of revelation, a mode of knowledge by which the pneumatized intellect participates in the knowledge that God has of himself in his Word. It is true that, in St. Paul, this experience has an exceptional character; it is willed by God as a norm and doctrinal reference for the Christian faith, without constituting a “second revelation”. Nevertheless, the very existence of such a mode of knowledge proves that the Christian religion does not reject the principle a priori. Now, this mode of knowledge, which realizes the perfection of faith (compatible with the human state), is the one to which Paul gives the name of gnosis. Obviously, it doesn’t present itself in this manner in every “gnostic”, neither does it attain the degree of Paulian gnosis, nor especially its (extrinsic) character as an objective norm for a traditional community (which makes St. Paul a “pillar of the Church”), but it necessarily follows from this possibility in principle. And this is why it is so important that Christianity counts precisely St. Paul among the pillars of the Church. Paul, who “does not know Christ according to the flesh”30.

However, we should not consider gnosis in St. Paul only in its charismatic and interior aspect. It is certainly the most profound and decisive dimension, but not the only one. As the name indicates, Paul’s “gnosis” is also a knowledge in the first sense of the term, which implies a properly intellectual activity, capable of being formulated and expressed in a clear and precise way. From this point of view, St. Paul contrasts glossolalia, the indistinct and inarticulate “speaking in tongues”, with “speaking in gnosis”, which uses the signifying articulations of language to transmit knowledge, a doctrine, and, consequently, to “edify” the community (1 Cor., XIV, 6-19). Gnosis is both ineffable and interior, a spiritual state, as well as formulable and objective, i.e. a doctrinal corpus. From this point of view, it is transmissible and can be the object of a tradition. Let us go further. The specificity of gnosis lies precisely in the conjunction of these two aspects. True gnosis is neither an abstract theory, a vain conceptuality that is illusorily satisfied with its own formulations, nor a confused mysticism, easily entrenched in the incommunicable. We can understand the importance that this term had to take on in the eyes of the first Christians, and later, in the first Fathers of the Church. In it was formulated something irreplaceable and infinitely precious: the affirmation of a kind of “internal verification” of the doctrine externally revealed and believed, the possibility for “theology”31 to be something other than a simple rational exercise, and to reach an intellective and savory experience of dogmatic truth — in short: a sacred intellectuality.

Such are the reasons that lead the early Fathers to use this term, although they had other words at their disposal to express the idea of knowledge. This is the case, first of all, for St. Clement of Alexandria, the greatest doctor of Christian gnosis (thus called), who presents it to us at once as a secret tradition taught by Christ to some of the Apostles32, as consisting in the interpretation of the Scriptures and the deepening of dogmas33, and finally as the perfection of the spiritual life and the fulfillment of the Eucharistic grace34. This is also the case with Origen, who, however, in the Against Celsus, also uses terms such as dogma, didaskalia, episteme, logos, sophia, theologia, etc., but who maintains the use of “gnosis” and “gnostic” even though he is fighting against a heretical Gnosticism, which leads him to the statement that “Christians have not been afraid to use the same vocabulary as the gnostics”35. We see the same attitude in St. Irenaeus of Lyons, whose Adversus Haereses fights the “gnosis with a false name” to establish the “true gnosis”. And it is the same for St. Dionysius the Aeropagite or St. Gregory of Nyssa. Thus, there has undoubtedly been an authentically Christian gnosis.36 And undoubtedly it was a great misfortune for the West that the Latin language did not contain any equivalent term to translate gnosis, because neither agnitio or cognitio nor scientia or doctrina had received from their Biblical, and then Pauline use, the sacred meaning of the Greek term.37 This semantic inferiority was obviously to favour the appearance and development of a theological rationalism which necessarily led to the anti-intellectual reactions of existential theology and, finally, to the disappearance of the doctrina sacra.

But after the Biblical and Pauline-patristic use of the word gnôsis we must come to its heretical use, since it is this that gave birth to what is called “Gnosticism”. This use already appears in St. Paul, when he denounces the “gnosis with a false name” (1 Tim., VI, 21). Similarly, John’s insistence on defining the divine “knowing” (ginôskein) can be understood as a warning against an alteration of the Christian gnosis. However, in the present state of our documentation, it is impossible to affirm the existence of a defined and organized Gnosticism in the age of the New Testament. As has been emphasized many times38, it is a question of tendencies, of gnosticising germs, not of a declared and constituted heresy. Let us not try to make the texts say what they don’t. And besides, the thing is self-evident. The extraordinary gnostic power of the manifestation of the Word in Jesus Christ could not fail to generate excesses in certain minds too weak to bear the intoxication. This is how the charismatic complexity of the gnostic experience was to develop, and how the refusal of “Christ according to the flesh” (along with that of the corporeal creation) was to cement itself, seeing that gnosis conceives itself as a grace of knowledge experienced in the interiority of the soul. In fact, he who says knowledge, says degrees of knowledge; and he who says grace given, says giver: the degrees of gnosis require therefore a hierarchy of givers, from whence the multiplication of divine intermediaries and the indefinite complication of angelology and cosmotheology. In addition, the dramatic overemphasis of spiritual interiority, which is highlighted by the esoteric elitism of the sects, lead to the rejection of the Word-made-flesh, and, consequently, to a “microcosmism” and the contempt of the Creator, the evil God, reduced to his demiurgic function.

Yet, the Christic gnosis is precisely characterized by its unity and simplicity. The divine intermediaries are reduced to the uniqueness of the Word-made-flesh (St. John), the Mediator between God and men (St. Paul). In relation to the pre-Christian doctrines of “universal gnosis” — whether Jewish, Hellenistic, Egyptian, or possibly Near Eastern — this is a great novelty. Christ is himself the gnosis of God, and this gnosis, having taken on a human body, manifests itself to all men, thus achieving a dazzling metaphysical short-circuit. All the degrees of knowledge and therefore of realities (the multiplicity of aeons) are synthetically “recapitulated” in Christ39, who thus offers a direct path to the gnosis of God. Moreover, although the gnostic experience necessarily remains something interior, and therefore esoteric, since it is the work of the Holy Spirit, it is nevertheless immediately proposed to everyone. By these two characteristics, the Christic gnosis operates a kind of anticipated restoration of the golden age and of the Edenic state. This is precisely what the excessive Gnostics cannot accept. What struck them and converted them, in a way, was the new and irresistible force of the Christic manifestation: it is visibly driven by the power of the Spirit. But they live this newness according to old patterns: they want to put the new wine in old wineskins. This new force to which they cannot remain insensitive, by its message of pure interiority, awakens in them the echo of ancient doctrines, either because they have known them directly, because they have been initiated into them and come from them, or because they have only heard about them, and their conversion to Christianity has led them to rediscover them and to become more and more interested in them. Such is, we think, the probable origin of what is today properly called Gnosticism, and whose historical existence is attested to us, around the second century, by the writings of St. Clement of Alexandria, St. Irenaeus of Lyon and St. Hippolytus of Rome. We see in it a phenomenon of revival of ancient and diverse doctrines under the shattering and revealing effect of the Christic manifestation in which they heard an irresistible call to spiritual interiority; for this is the most central meaning of the message of Jesus, the incarnate Word. This call, which resounds in every ear with such imperious and obvious accents, entered into consonance with many esoteric traditions, more or less dormant, or decadent, or sclerotic. The light of the Word suddenly illuminated them, making them emerge from the darkness, and brought back into memory their living meaning which seemed irretrievably lost. Thus, refusing to implant themselves onto the trunk of the Christic olive tree and to be carried by the true root of gnosis, they wanted to do the opposite, to graft the Christic branch onto the trunk of the old traditions, only to benefit from its vitality and to revitalize their old traditions.40 Our explanation cannot claim perfect certainty, but it does have the merit of plausibility. It is also consistent with the fact that, on the one hand, Gnosticism is a Christian heresy, and, on the other hand, doctrinal fragments of all origins and often of pre-Christian provenance can be found in it. Finally, it is based essentially on the consideration of the powerfully gnostic character of the Christic manifestation, which, it seems to us, has been overlooked until now.41

As we can see, the stakes of this formidable question are not small, and that is why we had to dwell on its history. It is highly significant that the first Christian heresy was Gnosticism, and in a certain way the whole history of the West was changed by this fact. For heretical Gnosticism, although it disappeared almost entirely in the fifth or sixth century, at least succeeded in one thing: it discredited definitively the New Testament term “gnosis” and, in so doing, well-nigh completely obscured the simple idea of a sacred intellectuality. And we believe that if the work of René Guénon has a meaning, it is not only to rehabilitate the notion of gnosis, but, more profoundly, to give us back the living and luminous intuition of it. However, before showing what the situation and the function of true gnosis in Guénon’s work actually is, we must ask ourselves what led him to adhere to the most questionable neo-Gnosticism in the first place, and what the meaning of this rather confusing episode was.

II. The Encounter with the neo-Gnostics

It must be noted that the beginning of Guénon’s interest in Gnosticism and gnosis seems to correspond quite precisely with that of his time, that is to say, with the idea of it that had been formed by a certain cultural fad between 1880 and 1914. Let us note that it is also in this period that the scientific historiography of Gnosticism was established, with its two great tendencies, that of Harnarck on the one hand, who sees in Gnosticism “a radical and premature Hellenization of Christianity”42, a Hellenization that the Greater Church will successfully achieve with more wisdom and slowness, and that of Bossuet and Reitzenstein on the other hand, who, struck by the resemblance of Christian Gnosticism with Egyptian, Babylonian, Iranian and Hermetic religious manifestations, speak of a pre-Christian Gnosis and see in the Gnosticism of Valentinus, Basilides or Marcion, a kind of “regression of a Hellenized Christianity towards its oriental origins”43, in short, an “orientalization”44 no less radical than the Hellenization of Harnack. Now, this flourishing of Gnostic historiography goes hand in hand with a certain fashion for Gnosis, which already appeared in the 18th century, but which defined its essential features especially in the first part of the 19th. It was at this time that the more or less “occultist” meaning of this term became clearer, a meaning that it would henceforth retain in the use made of it by most pseudo-esoteric circles. This was not the case in the 17th century. At that time, Fénelon could still try to use the perfectly orthodox vocabulary of Clement of Alexandria to identify the mysticism of pure love with the gnosis of the Fathers of the Church. Certainly, his opuscule La gnostique de saint Clément d’Alexandrie, in which he provides a masterly exposition of the doctrine of the great Alexandrian, was to remain unpublished for a long time, Bossuet having evidently forbidden its diffusion.45 Nevertheless, Bossuet himself does not take offense at the use of the term and only tries to bring its meaning back to the level of common theology: “I do not see,” he says, “that it is necessary to understand under the name of gnosis any other finesse nor any other mystery than the great mystery of Christianity, well known by faith, and well understood by the perfect due to the gift of intelligence, sincerely practiced and turned into a habit”.46 Similarly, Saint-Simon attests to us that the term gnosis designated, at the court of Louis XIV, the doctrine of Fénelon47, however, the “compromising” character of the term seems to us to have become accentuated with time. The reasons for this are not difficult to assume.

The failure of Fénelon in his effort to revive the gnosis of St. Clement of Alexandria by bringing it closer to Theresian and Sanjuanian mysticism as well as to the doctrine of pure love, left only one meaning of this term, the condemned one. In fact, the dictionaries of the time, that of Moreri, or the famous Dictionnaire of the Abbé Bergier48, do not contain any article on gnosis, but only on the Gnostics which deals primarily with the heretics of this name. The ordinary meaning is hardly mentioned. No doubt official Catholicism was thus convinced that it had won the battle against gnosis, and that, by banning the term, it had secured a definitive victory over the thing it designates. But this is not the case. The condemnation of all gnosis would have been effective only if it had been imposed on a resolutely Christian society. Instead, such a relentlessness — which did not shrink from any slander, particularly with regard to morals — could only serve to bring this heresy to the attention of libertines and malicious people. And this is exactly what happened. Little by little, the heresiarchs became heroes of free thought. One saw in them either Christian philosophers who were already trying to shake off the yoke of dogmatic discipline and who couldn’t be satisfied by the credulity of the vulgar, or pagan philosophers anxious to apply the demands of reason to the obscure images of the faith. Besides, the esoteric elitism of Gnosis flatters the vanity of the libertine. The more profoundly the society of the ancien régime was dechristianized, the more religion was reduced to a simple facade, still omnipresent, but whose “crude deception” was less and less tolerated: Good for the simpleton, as Voltaire affirms, who on Sundays amuses himself by playing the country priest in front of his peasants, its power is without effect on the superior spirit which turns, with a feeling of connivance, towards the ancient heretics, and even, beyond Christianity, towards ancient paganism. From this point of view, all esotericism can only be heterodox and a vehicle for the hopes of the human race in its long struggle towards the “light”. Then came the French Revolution, whose unleashed Satanism dealt the Catholic Church, the oldest institution in the West, the most terrible blows in its history. In one year, between 1793 and 1794, this institution completely disappeared from French soil49, and it will never recover its former splendor. With the facade knocked down, in the spiritual desert of a sinister time like no other, and with no way to refill the cracks torn into it by an extremely insane rhetoric, a certain mystical neo-paganism could find some entries.

A little later, the current of Romanticism developed in Germany, which, in certain respects, was the antipode of revolutionary atheism, but which would end up combining with it to constitute a kind of esotericism that was eventually anti-Christian. This romanticism, by rediscovering Meister Eckhart and Jakob Boehme, brought the idea of a purely interior spiritual knowledge back to honor, to which it gladly gave the name of gnosis. The best example, in this respect, is undoubtedly that of F. X. Baader, who distinguishes clearly between a pseudo-gnosis of diabolical origin, and the true Christian gnosis: “It is true that there is a pseudo-gnosis,” he says, “and the work (of L. CL. de Saint Martin) (...) speaks to us clearly enough of such a school of Satan spreading terribly among us; but this also means that there is, and has always been, a true gnosis”50. In the same way, Hegel defines the Boehmian work as a gnosis, which must, however, be perfect and transformed into pure philosophy.51 It is conceivable, then, that, in the intense circulation of ideas that took place in Europe during the first half of the 19th century, gnosis gradually came to designate an esoteric knowledge, superior to that of Christian dogmatics, and which renders useless all official religion because it dispels the mystery. This gnosis, the mystical foundation of the anti-clerical ideology, is convinced to reconnect with a secret tradition, the exemplary victim of the ecclesiastical hatred, and to rediscover the nourishing earth of our most authentic cultural roots, those that Judeo-Christianity had not poisoned, or that the Roman centralism had not succeeded in extirpating. An unmistakable testimony to this conception is the article that Pierre Larousse’s Grand Dictionnaire Universel devotes to Gnosticism (the term had already been adopted): “One would be mistaken (...) to believe that gnosis is essentially a Christian phenomenon. By its origin, its goal, and its efforts, it is much broader than any religion could be; it is free thought seeking to explain at the same time the world, society, beliefs, and customs, all with the help of tradition; which demonstrates that one should not confuse here free thought with rationalism”. Then, after having affirmed that its resemblance to Buddhism proves its Indian origin52, he declares: “Gnosis was not a heresy, but the philosophy of Christianity itself ; (...) to the Christians Gnosis said: ‘your leader is an intelligence of the highest order, but his apostles did not understand their master, and, in their turn, their disciples altered the texts that had been left to them’”.53

Such is, approximately, the idea of “gnosis” held by those whom we have called “anti-clerical mystics”, and with whom the young Guénon came into contact. They speak of it with all the more assurance that they disdain to inquire about it historically, convinced that they are the only ones who really know what it is all about. However universal their conception of gnosis may be, they intend to place themselves in the doctrinal continuity of what was beginning to be called Gnosticism, that is to say, of the heretical Christian schools. This doctrine is generally presented as an emotional reaction to the scandal of the existence of evil. This is undeniable, but insufficient. The objective evil present in creation, which appears to them irremediably soiled, is so keenly felt as unjustifiable only in correlation with the dramatic overemphasis on saving interiorization: these two excesses, one objective, the other subjective, condition each other. The duty of interiority repudiates all material creation as evil, and the decay of creation leaves no other salvation than the interior flight. The result, as we have shown elsewhere54, is an anti-creationist angelism which is necessarily accompanied by a Christological docetism: how could God have become truly flesh, if the flesh is entirely evil? Consequently, the Biblical creator is only a demiurge, an evil god, who should be rejected along with the entire Old Testament and the theological rabbinism of St. Paul. These themes are well known. They reveal, with regard to the metaphysical doctrine as Guénon himself taught it, not only a more bhaktic than jnânic thought, but also a radical misunderstanding of the mystery of divine immanence in cosmic exteriority; for, as the Koran teaches: “He is the First and the Last, and the Exterior and the Interior, and He knows everything infinitely” (LVIII, 3).55 As we can see, according to the Koran, the “infinite gnosis” of God consists precisely in its radical unity and the strict implication of immanence and transcendence, the external and the internal. However, some of these ideas are found in the very first texts of Guénon-Palingénius, and one can see why he was able to suggest one day that he had nothing in common with the one who had expressed them.56

We will not go into detail about the history of the renewed Gnosticism as it emerged in France at the end of the 19th century. This history is still to be written. Yet, its main elements can be found in the various works devoted to Guénon, and which explain how Guénon was led to enter into contact with this Gnosticism.57

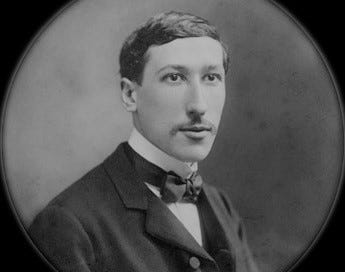

Around 1880, Lady Cathness, Duchess of Pomar and a member of the Theosophical and Esoteric Christian Society58, organized in her private mansion in the Rue Brémontier in Paris, spiritualist sessions where one liked to evoke the spirits of the great departed: Simon the Magician, the father of Gnosticism according to St. Irenaeus, Valentine, Apollonius of Tyana, etc. These sessions were sometimes attended by an archivist and man of letters with an impressionable and somewhat unstable temperament, named Jules Doinel. “One evening in the autumn of 1888”59, the spirit of Guilhabert de Castres, Cathar bishop of Toulouse60, manifested itself and gave J. Doinel the mission of restoring the Gnostic Church, and, for that purpose, invested him with the function of patriarch.61 Other revelations and some verifications convinced J. Doinel of the authenticity of his initiation. At the instigation of a friend, Fabre des Essarts, a Gnostic assembly was held in Paris which recognized Doinel as patriarch under the name of Valentin II. Later he himself confered the episcopal dignity to Fabre des Essarts (Synésisus)62, to Gérard d’Encausse (Papus), founder of Martinism, and to a few others. Doinel, however, seems to have always been eager to approach the Gnostic Church to the Catholic Church. In 1894, he even went so far as to abjure and to hand over his episcopal pallium to the Bishop of Orleans.63 This is why, in 1895, Synésius succeeded him as patriarch of the Gnostic Church, and in turn conferred an episcopal consecration on Léon Champrenaud, Albert de Pouvourville, Patrice Genty, etc. It was during the Spiritualist and Masonic Congress of 1908 that Guénon met Fabre des Essarts. He asked to enter this Gnostic Church and, in 1909, he was consecrated bishop of Alexandria under the name of Palingenius64. Synésius then founded the review La Gnose, the direction of which he entrusted to Guénon and whose publication stopped in February 1912. These are the facts, as far as we have been able to reconstruct them.

As for the doctrine of the Gnostic Church, it is in every respect in conformity with the theses of the Gnosticism of the first centuries: anti-Judaism and anti-Jehovism, renewed accusations against the Fathers of the Church who “twisted in a thousand ways the teachings they received”, anti-clericalism, etc.65 Unquestionably, these theses are in contradiction with Guénon’s later teaching. How then could he make them his own? Guénon’s successive or simultaneous affiliations with various pseudo-esoteric organizations are usually explained as an investigation to verify their initiatory claims.66 Moreover, Guénon himself presented things in this way, speaking of “the investigations we had to make on this subject...”, that is, on the subject of initiatory regularity.67 It is true that in another text he affirms that: “If we have had to penetrate, at a certain time, into such and such circles, it is for reasons that concern only us”68, which does not contradict the previous affirmation, but is certainly less explicit. We have recalled, apart from this, the declaration he had made to Noëlle Maurice-Denis Boullet, according to which he had entered the Gnostic Church to destroy it.69 As it seems to us impossible to dispute the convergent significance of these assertions, are we forced to admit that Guénon was earnestly investigating the esoteric claims of the organizations in question, and was trying, for that purpose, to penetrate inside each of their associations? Was a critical examination of their declared doctrines, which were obviously anti-traditional, not sufficient? No doubt it must be assumed that certain appearances may be misleading or confusing in this respect.70

It should therefore be concluded that, contrary to our previous supposition, Guénon never made the doctrines in question his own and that he only seemed to accommodate them for the time necessary for his investigations. This conclusion seems to be confirmed by certain texts of Palingenius who, for example, declares in 1911: “we are not neo-Gnostics (...) and, as for those (if they still exist) who claim to hold to the sole Greco-Alexandrian Gnosticism, they do not interest us at all”71. It is also certain that — as has often been pointed out — in many of the articles of this period we find doctrinal elements identical to those formulated by the mature Guénon. What is more, Guénon himself declared, in 1932, following the above-mentioned text on the personal reasons he had for “penetrating such and such circles”: “whatever publications we have published articles in, whether ‘at that time’ or not, we have always set out exactly the same ideas on which we have never varied”.72

And yet, it is very difficult to reconcile certain assertions of the period from 1909 to 1913 with those of the later work. If we believe, as we’ve said at the beginning, that on the essentials, that is to say, on pure metaphysics (or gnosis) Guénon has never varied, and for good reason, we are nevertheless obliged to note that his judgment on what we will broadly call the traditional forms has changed.

A few years ago, in a very judicious article, Jean Reyor underlined how much the publication of certain texts prior to 1914 could confuse the reader of Guénon, who, “in his mature age, no longer intended to be in agreement with all the positions taken in his youthful writings”73. When he affirms, for example, in the review La Gnose that “Tradition is by no means exclusive of evolution and progress”, that the goal of the Great Work is “the integral accomplishment of progress in all fields of human activity”, that Masons do not have to recognize “the existence of any God”74, that moreover “the God of religions (...) is not only irrational but even anti-rational”, and that the “anthropomorphic god of the Christians” cannot be assimilated to “Jehovah (...), the hierogram of the Great Architect of the Universe himself”, whose name can be replaced by that of Humanity75, and other such oddities, one has the right to ask oneself, without malice, if these remarks are reconcilable with what one finds in The Crisis of the Modern World or in The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times. It is impossible to answer yes, even if Guénon specifies that, by humanity, one must understand “Universal Man”, and that reason can be considered as “superior reason”, according to an expression of St. Augustine, which is also the case for the word manas in Shankara or in the Samkhyâ school.76

But, to tell the truth, these divergences concern more a general tone, revelatory of an attitude, rather than particular doctrinal points. The use of the vocabulary of anti-clerical rationalism proves above all that Guénon had not yet freed himself from certain influences and certain circles whose language he, in some respects, adopted. This is something he won’t do afterwards, from 1911-1912, when he definitively breaks with the Western organizations to which he belonged, or proceeds with their dissolution himself. This change of attitude does not only concern the notions of progress, evolution, and rationalism, which one would characterize quite well as “the ideology of free thought”. It also concerns something much more important, namely Guénon’s attitude towards religion in general and Christianity in particular. Without doubt, this attitude will remain very critical. But one perceives in the young Guénon an indifference — not to say a contempt — towards religions and their God, which seems to us to be absent from the great works of his maturity. What Palingenius lacks is not the notion, but perhaps the living and concrete sense of Tradition, and thus the respect for the sacred forms in which it is expressed. Certainly, the doctrinal content of the great works is already more than outlined in the articles of La Gnose, and one is right to point this out. But the climate of his thought has changed somewhat. In 1911, Palingenius asserted: “we cannot conceive of metaphysical Truth in any other way than as axiomatic in its principles and theorematic in its deductions, i.e. as exactly as rigorous as mathematical truth of which it is the unlimited extension”77. In 1921, René Guénon wrote: “Logic and mathematics are what, in the scientific domain, provides the most real correspondences with metaphysics; but, of course, by the very fact that they enter into the general definition of scientific knowledge (...) they are still very profoundly separated from pure metaphysics”78. Meanwhile, the transcendence of metaphysics over all the other disciplines has been considerably accentuated because its nature as a sacred tradition and its primordial origin (already explicitly affirmed), have led Guénon, perhaps as a result of a certain event, to come to a more distinctly hierarchical awareness of its principial pre-eminence.79

A final example will suffice to convince us of this change of tone and of the distancing of his thought from the “Gnosticism” of his youth. It is provided to us by the famous article The Demiurge, considered as Guénon’s first doctrinal work, proving that, as it is commonly claimed, by 1909 he was in full possession of his doctrine. However, this is not exactly true, and if we read this text carefully, we can observe a considerable divergence from the later texts, at least on one point, which is quite significant.

We will already point out that the very title of “Demiurge” and the evocation of the problem of evil at the beginning of the article, to which this Demiurge is charged with providing a solution, are typical of Gnosticism: the Demiurge is the creator of the evil world. In fact, when we look at the details of the presentation, we see that the central idea, which is basically orthodox, could do without the language with which it is clothed. What proves this is the complete disappearance of this “character” in his later works.80 When, in 1909, he identifies “the domain of this same Demiurge” with “what is called Creation” if “all elements of Creation are contained in the Demiurge himself” and who can therefore be “considered as the Creator”81, in 1921 the identification of the Demiurge with the Creator God is regarded as a “theological heresy” and “metaphysical nonsense”82. This nonsense is moreover proper to Gnosticism: one should not, says Guénon, “assimilate (the Great Architect of the Universe who is “only an aspect of the divinity”) to the Gnostic conception of the ‘Demiurge’, which would give it a rather ‘malefic’ character (...)”83. Between the Creator and the Demiurge “it would at least be necessary to choose”84.

But the point that seems most significant to us concerns what Guénon calls, in The Demiurge, the “pneumatic world”, distinguished from the “hylic” and “psychic” worlds. Approaching these gnostic (and Pauline) names to the Vêdânta doctrine, he writes: “He who has become aware of the two manifested worlds, that is, of the hylic world, the set of gross or material manifestations, and of the psychic world, the set of subtle manifestations, is twice born, Dwidja ; but he who is conscious of the unmanifested Universe or the formless World, that is, the pneumatic World, and who has reached the identification of himself with the universal Spirit Âtmâ, he alone can be called a Yogi, that is, united with the Universal Spirit”85. And, a few lines further on, he establishes the correspondence of these three worlds with the three states of wakefulness, dreaming, and deep sleep. In such a cosmology, manifestation thus comprises only two worlds, corporeal and psychic, the pneumatic world being unmanifested, and the “Pleroma, neither manifest nor unmanifest”. Now, as we know, according to Man and His Becoming, universal manifestation comprises three worlds, the third being constituted by the intelligible or informal realities. Compared to the Gnostic conception of The Demiurge, the manifested universe is thus expanded by an additional degree, the one that India calls Mahat or Buddhi. Hence, the state of deep sleep (sushuptasthâna), which is the state of Prâjna (the “knowing one”), no longer corresponds only to the unmanifested degree of pure Being, but also encompasses the informal manifestation: “Buddhi must in a certain manner be included in the state of Prâjna”86.

However, what should be noted above all is that the addition of a degree of reality to universal manifestation completely changes its meaning: the cosmic pessimism of Gnosticism is challenged, for if creation contains the pneumatic or intelligible, then there is at least one degree of the universe which shines in the beauty of its created perfection and where its fundamental goodness is revealed. Essences, as informal realities, are “ultimately nothing other than the very expression of Âtmâ in manifestation,”87 and conversely, we may say, the expression of manifestation, if not in Âtmâ, then at least in its most immediate proximity: paradisiacal creation illuminated directly by the divine Sun.88

One sees all the importance, which is truly decisive, of the affirmation of the intelligible world which, alone, can save the cosmos from its indefinite dispersion to the outer darkness, while at the same time saving human knowledge from its disintegration into the insignificance of nominalism. Aristotle, who denies the proper reality of essences, is the true father of Ockham.

We have now said enough about Guénon’s relationship to Gnosticism. From this point onwards, his attitude will not vary and will even become more pronounced. We could summarize it in the following two points: Firstly, the condemnation and definitive rejection of the neo-Gnostics, and secondly, the prejudicial and invariable distinction between gnosis and Gnosticism. And if gnosis is defined as metaphysical knowledge par excellence, Gnosticism is, with some divergences depending on the texts, defined in a rather pejorative way, as the totality of the heretical schools that historians designate with this name. The most explicit text that Guénon devoted to it is found in East and West. He states, in particular: “It is rather difficult to know today the precise nature of the somewhat varied doctrines which are classified under this generic term of ‘Gnosticism’, and among which there would no doubt be many distinctions to be made; but, on the whole, it appears that they contained more or less disfigured Eastern ideas, probably badly understood by the Greeks, and clothed with imaginative forms which are hardly compatible with pure intellectuality; one can certainly find without difficulty things more worthy of interest, less mixed with heterogeneous elements, of a much less doubtful value, and of a much more assured significance”89.

If we now ask ourselves about the event to which we’ve alluded earlier and which would have played the role of a catalyst in Guénon’s attitude towards the pseudo-esotericism of religious forms, we shall reply that it is most probably constituted by his attachment to Sufism. It was in 1912, according to the indications provided by the dedication of The Symbolism of the Cross (a date which is also confirmed by a letter), that Guénon received the initiation.90 We believe this event to be decisive, not from the doctrinal point of view, but from the spiritual point of view, i.e. for what concerns the commitment of the entire being to the Truth. How, indeed, can one fail to notice that it was at this date that Guénon broke definitively with the “margins” of esotericism in order to join a regular initiatory lineage? It is also this initiation that gives him a more vivid and concrete awareness of the requirements of the traditional point of view, since it seems that, according to the excellent title of Jean Robin’s book, René Guénon never wanted to be anything other than a “witness of Tradition”. There are undoubtedly other incidents to be noted which are no less significant (for example, the abandonment of the pseudonym “Palingenius” for that of “Sphinx”). In any case, this event seems to us analogous to the one that will occur in 1930 with his departure for Cairo, and which will give him the opportunity to immerse himself — as much as his nature allowed — into a truly traditional atmosphere. “Blessed are those who have not seen and have yet believed”. But there are things that one understands only after having seen them...91.

III. The Mystery of infinite Gnosis

The distinction between gnosis and Gnosticism, to which Guénon henceforth adheres, has become the rule. In fact, it is known that the participants of the International Colloquium of Messina on the origins of Gnosticism agreed to define this term as designating “a certain group of systems from the second century AD that is conventially named as such”, while Gnosis means “the knowledge of divine mysteries reserved for an elite”.92 This distinction is not sufficient, however, to make clear the true nature of gnosis and to free it from its Gnosticist corruption. Besides, if the preceding considerations only resutled in confirming the perspicacity of Guénon’s judgment on the matter, they would be of very little interest. In reality, what is much more important is the very conception of gnosis, that is to say, of metaphysical knowledge (jnâna), which Guénon has exposed and developed, and even more, which he has made to “exist” before our very eyes, and whose meaning he has consequently restored to us.

In order to show the true meaning of orthodox gnosis, such as Guénon has formulated it, as well as its importance and function, it would in fact be necessary to retrace the whole history of Western philosophy93, from its Greek origin to its most curious contemporary forms. Only this history, we believe, which is also, in certain respects, that of Christian theology, at least since the end of the Middle Ages, would allow us to grasp what is at stake in this question. For want of this, we will merely content ourselves with a brief characterization.

The idea of gnosis is that of a supernatural and unifying knowledge of the divine Reality. And these three elements are indeed necessary for its definition, i.e., firstly: Divine Reality or infinite and perfect Reality, because all knowledge is specified by its object and that of gnosis is none other than the Object par excellence, the absolutely real. Secondly: unifying or identifying, because, unlike any other knowledge, there’s only gnosis if there’s a transformation of the knowing subject and a union with the Object known: whereas knowledge, operating by abstraction, usually leaves the very being of the knower outside of itself, here it takes place precisely only in a deifying participation in what it knows. Thirldy: it is supernatural, or metaphysical, or supra-rational, or sacred knowledge, because, even though it is knowledge, like any speculative act, it is radically distinguished from it by its mode, which is that of the pneumatized (or spiritual) intellect; in fact, it is distinguished from the other modes insofar as, in it, the perfection of all cognitive aims is realized.

This conception of a sacred intellectuality is basically that put forth by Plato and neo-Platonism: a knowledge that is a conversion and which engages the whole being, so that the degrees of knowledge are, as the many states of the being, hierarchically ascendant. This is what the symbol of the Cave teaches us, as well as the Plotinian doctrine of hypsotases. And such is, quite explicitly, the definition that Plato gives of philosophy, a conception which was bound to run up against two kinds of objections, the ones in the name of intellectuality, and the others in the name of the sacred.

The objections concerning the speculative order are raised by Aristotle, who inaugurates, in the history of Western thought, what can be called “profane science”, that is to say, an exclusively abstract functioning of knowledge.94 With a doubt, science is still objectively linked to metaphysics, at least to some principles of an ontological order. But what comes first is the study of logic (the Analytics) of which Aristotle is the inventor. Metaphysics, here, has no other interest than to found physics. And, whether physics or metaphysics, knowledge is one and only differentiated in function of the various modalities according to which it abstracts the known reality.95 We see all that separates such a conception from that of Plato. For Plato, to know is to know that which is. The truth of knowledge varies according to the reality of its object. There are thus essentially degrees of knowledge corresponding in rigorous manner to the degrees of reality, so that any lower degree is ignorance with respect to the higher: there can be no true knowledge of that which not truly is, that is to say, of becoming. Only knowledge of the Absolute (the Unconditioned, Anhypotheton) is absolutely knowledge. It is that of the Supreme Good “beyond being” (epekeïna tês ousias, Republic, VI, 509b), but which requires the actualization of the intellect (nous) and the abandonment of discursive knowledge (dianoïa). In other words, because all true knowledge is a desire for being, the intellect cannot (truly) know anything with which it cannot identify. But can man become a stone, a tree or a cat? No. Consequently there is no perfect knowledge of the stone, the tree or the cat (as sentient and physical beings).

In contrast, it is in the physical realm that Aristotle wants to obtain a scientific certainty. We can see in which sense we must understand the formula of the De anima that Guénon was so fond of quoting: “the soul is all that it knows”96. It cannot have the meaning of an entitative union of the soul with its objects of knowledge. Neither can it be considered as an unconscious revelation of Aristotle, signifying more than he aimed to express. In fact, the exact formulation always contains the adverb pôs, “in some way” (quodammodo).97 And if the soul, in the act of knowledge, can be, quodammodo, all things (stone, tree or cat), it is precisely because the act of knowledge effects a radical separation of being and intellect; in other words, it is because it is nothing (entitatively) of what it knows, that the soul can (intentionally) identify itself with everything known. Knowledge, for Aristotle, is achieved through a process of abstraction that “de-existentiates” the intelligible form and removes it from the real and concrete being, thus allowing it to exist in the soul to which it is united by “informing” it. The intelligible form is then nothing other than what we call a concept.98 But if, as far as the sensible world is concerned, the Aristotelian analysis merely expresses the pure and simple truth, it is not the same for the knowledge of the intelligibles (whose proper existence Aristotle denies) and especially of the Supreme Intelligible that is God, which the philosopher acknowledges in a certain way, without however drawing all the consequences from it. This difficulty of Aristotelian thought is clearly shown in the classical problem of knowing whether there are, for Aristotle, two primary philosophies, ontology (or general metaphysics) and theology (or special metaphysics): is the “being qua being” being in general or God?

However that may be, in the West, it is Aristotle’s philosophy that provides the general conception of what a science should be, while, at the same time, it is this science which provides the model of all true knowledge. To know is to know an object, i.e. something which, in its own being, is radically other than the being of the knowing subject. All knowledge implies this ontological distinction, otherwise the objectivity of science is called into question.99 And doesn’t this conception seem to agree quite marvelously with the Christian Revelation? We meet here with the second kind of objections that we had announced above, those concerning the sacred.

We cannot dwell at present on the considerable changes that the irruption of Christianity brought about in the cultural field of Antiquity, and whose study is still nowhere near complete. Let us at least say that this irruption had the effect of profoundly modifying the very notion of the sacred and of salvation. In the very measure in which salvation (which need not be distinguished here from deliverance) takes place through faith in Christ who communicates his grace, thus raising human nature to its deifying perfection, simple intellective knowledge is stripped of its salvific dimension. This knowledge can therefore only concern the intelligence, not being itself, the immortal person, which is the exclusive domain of religion. Hence the desirability of a doctrine which ontologically “neutralizes” and “secularizes” knowledge, leaving human existence entirely to religion. In this manner, science and faith, philosophy and religion, nature and supernature, reason and grace, are brought into agreement through the distribution of their respective competences.

However, this equilibrium, which flourishes exemplarily in the work of St. Thomas Aquinas, is fragile, and this from two almost antinomic points of view, the one of which refuses the real distinction of science and faith, while the other accentuates it to the point of contradiction; two points of view which, moreover, condition each other. In any way, it is not even really a question of two points of view which are possibly comparable; rather, it’s a requirement of the nature of things in the first case and a result of their “culture” in the second one. Indeed, the point of view of non-distinction does not result from a theoretical decision, but imposes itself necessarily: faith is knowledge in its very essence, and knowledge inevitably comprises a dimension of faith, insofar as it is the adherence of a being to what it does not see yet. One thus notes, in science as in faith, the presence of a common and irreducible core of gnosis. Nothing can durably modify this fundamental fact. As for the second point of view, it only develops, in accordance with the history of Western thought itself, the methodical separation of science and faith by radicalizing it as far as the nature of things allows it. This means that science is progressively defined as non-faith, and faith as non-science.

Faith proclaimed as a non-faith, this is the primary achievement of Cartesianism, which, despite some reservations, definitively marginalizes theology. However, it is not until Kant that this exclusion is philosophically integrated into the conceptual act as such, which means not merely a rejection of religious concerns (this had been aquired a long time ago), but an a priori rejection of the ontological dimension of knowledge, insofar as all faith is the adherence to a hidden being. In other words, Kantianism established the ontological neutralization of all knowledge as a principle. Being, the real by definition, is what cannot be known.

The theological repercussions of Kantianism, in spite of — or because of — Hegel's “pseudo-gnostic” reaction, will lead to the Bultmanian enterprise and to the pseudo-theologies of the death of God: any concept is an alienating abstraction, even that of God (or that of any dogma, Trinity or Incarnation); faith is a pure experience which has no other end than to awaken human existence to the awareness of its irremediable contingence.

Such is the intellectual situation of the Christian West (Europe and America), to which, as we believe, the providential manifestation of Guénonian gnosis has provided the remedy. And this is what we would like to show in conclusion.

This situation can be described as a gradual divorce of being and knowledge, a divorce that ends up being established as a principle. That this is not easy to remedy is proven by the the failure of the Hegelian and Teilhardian “gnosis”, the first one proposing to reconcile knowledge and being, the second one science and faith (or inversely, according to the points of view).100 It is not even enough to assert the contrary thesis to resolve all the questions that the philosophical and theological critique will inevitably raise. For philosophy, there is no knowledge that does not pose its object as a distinct reality, and the theme of “co-naissance”101 has for it only a poetic interest. For the theologian, to unite being and knowing, or to speak of a salvation for knowledge, is to discard revelation and grace, to give in to the abhorred gnosis and to fall inevitably into pantheism. However, the reader of Guénon does not have this feeling at all. No one has emphasized the idea of Tradition more than Guénon, and attached true knowledge to its divine source. Never — except by distorting his thought — can Guénon be drawn to the side of an intellectualist reduction of the metaphysical doctrine. Metaphysics is an intrinsically sacred science. It transcends all the formulations that are given to it and all human receptacles that receive it. It is very precisely the divine Word itself as “light illuminating every man who comes into this world”, that is, every being who attains the human state.

But this is not all. If one studies Guénon’s doctrine carefully, one realizes that metaphysical knowledge, in addition to this remarkable situation which decisively tears it away from the profane world and restores it to its proper order, is characterized in itself as an effective consciousness of the real, so much so that, for man, only that of which he has become effectively conscious is real, all the rest being defined as merely possible. Knowledge is thus “realizing”, not in the idealist sense that it creates the real, but in the sense that, only through it, there is, for the human being, the real. The real is rigorously correlative to the act by which one becomes conscious of it. It is not posited contradictorily in itself by a theoretical affirmation that forgets that the autonomy and independence of the real that it posits is exactly and necessarily dependent on the act by which it posits it, as the philosophical critic will take great pleasure in emphasizing. In other words, and to express ourselves less abstractly: any affirmation of the absolute and infinite Real seems to sin by excess and by defect: by excess since, being relative, it says more than it is entitled to; by defect, since this Absolute is nothing more than affirmation.102 To the second difficulty, Guénon answers by showing, in a very classical manner, that it is not the human intellect which affirms the divine Absolute, but the Absolute itself which affirms itself in each intellect: the Verbum illuminans. To the first difficulty, the answer is more “original”, or at least more explicit than is usual. And, in fact, it does not seem to have been formulated in this way before, even though it is presupposed by all true gnosis, and, first and foremost, by Shankarian jnâna. This “new” explanation is obviously demanded by the profound metaphysical obscurity of the present cyclic end, during which the prodigious development of mental prowess has progressively stifled the intellective intuition of implicit truths. We are at the time where it is necessary to “dott the i’s and cross the t’s” — we say this without the slightest illusion.

It is in The Multiple States of the Being that Guénon lays out this answer. Let us try to extrapolate it. The work begins with a chapter devoted to the famous distinction between the Infinite and Universal Possibility, a distinction which, moreover, has no reality except from our point of view, since, from the point of view of the Supreme Principle, Universal Possibility is nothing other than the Infinite; however, it is not arbitrary either, since it corresponds to two “aspects” of the Supreme, an analogously “active” aspect and an analogously “passive” one. This is not the place to investigate the origin of this distinction103, which is more Tantric than Shankarian104, but we must ask ourselves why Guénon introduces the concept of Universal Possibility. What is the point of it? What’s its purpose? Is the concept of Infinity not sufficient? Guénon gives a first answer by stating that the point of view of Universal Possibility constitutes “the minimum of determination that is required to make the Infinite actually conceivable”. In short, we cannot actually conceive the Infinite in itself. When we think of the Infinite, we actually think of “universal possibility", or in other words “that which can be absolutely anything”, “that whose reality cannot be limited by absolutely anything”, and this is basically another way of talking about the “absolute non-contradiction” of the idea of the Infinite, since the impossible is that which implies contradiction.105 We then learn that this minimal determination corresponds to an “objective” aspect of the Infinite, which Guénon identifies with the passive Perfection. In any case, Universal Possibility necessarily encompasses that which exceeds Being, since Being, or the principal determination, is inevitably counterposed to that which is not, and thus contradicted by it.106 Thus Being is not “beyond” all contradiction, it does not realize the absolute non-contradiction, which is another name for Universal Possibility. In order for the Supreme to be absolutely non-contradictory, such that nothing can contradict it, it is therefore necessary that it exceeds the first of all determinations and that it embraces what is beyond Being. This is why, for It, “to be able to be everything” means also the ability to be Non-Being. Such is the logic of the Infinite. It appears thus that the point of view of Universal Possibility is hardly a determination, which really begins only with Being, but that it is rather necessary to consider it as the universal determinability of the Principle, which, in Itself, is un-determined (or over-determined) even by the principal determination of Being.

However, the very concept of possibility harbors an ambiguity insofar as it derives its meaning from its opposition to that of reality. What is possible is that which “can be”, that is to say, that which does not contain any conceptual contradiction (like that of a circle-square, of a ram-goat, or of a gaseous vertebrate), but which is not currently realized, or which is at least considered apart from its current realization or non-realization.107 There is no doubt that scholastic philosophy considers the possible as designating the essences of creatures in so far as they are only in God, and thus “anteriorly” to all existentiation. To adopt this point of view is to affirm that there are only possibilities of creation (whose existentiation depends on the divine Will) on the one hand, and, on the other hand, that the possibilities have meaning only with regards to their realization. Therefore, one obviously cannot speak of the supreme Reality as Universal Possibility, which would imply that It is not actually real, nor can one speak of possibilities of non-manifestation. This is why Guénon affirms that the “distinction of the possible and the real, on which many philosophers have so strongly insisted, has no metaphysical value”108. But then, what is the point of talking about possibilities? And especially of possibilities of non-manifestation? Why not speak at once of non-manifested realities? — since there is in fact a metaphysical identity of the possible and the real, and, in dealing with the Unmanifested, we are surely at the metaphysical level par excellence. Does the term of possibility retain a meaning when it concerns the divine Metacosm, where everything is in permanent actuality? “Possibilities of manifestation” offers a clear meaning in relation to Manifestation, to indicate the relation of an eternal essence to its existentiation in a determined world. But how could there be existentiation at the level of the Unmanifested? Unless one means only possibilities that God doesn’t want to realize? But Guénon rejects this interpretation: the possibilities of manifestation define everything manifestable, whether it is manifested or not.